Rosslyn Castle

William St. Clair of Rosslyn began building the castle about 1304, and for the next 350 years it was strengthened, bombarded, rebuilt, extended, burned and almost destroyed. In 1650, Cromwell’s troops under General Monck left it in much the same state as we see it now.

Rosslyn Castle is perched high on a promontory of rock, hidden in a steep-sided wooded valley overlooking the beautiful River North Esk, just 8 miles from Edinburgh. It is surrounded on three sides by the river, and is only accessible by a narrow bridge crossing a 55-foot chasm, created by cutting through the neck of rock connecting the promontory to the ground behind.

Although it might have been difficult to assault, it was never secure against artillery. Instead, it became a high-status family home for generations of Rosslyn St. Clairs, until William, the ‘Last of the Rosslyns’, died in 1778. Eventually, after many years of decay, it was inherited in 1977 by its current owner, Peter St. Clair-Erskine, the seventh Earl of Rosslyn. It is now managed and let by the Landmark Trust to help cover the high cost of its maintenance, and they have published an interesting Rosslyn Castle History Album compiled by the Earl and Countess.

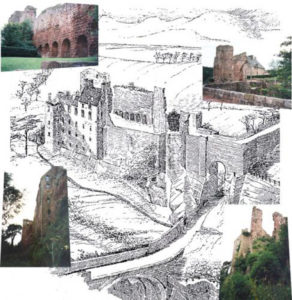

Photographs of the castle from different perspectives. Note the lower road crossing the Esk, which would have circled the castle, arriving close to the garden entrance between the house and the Keep. The middle of the bridge was destroyed about 1700, and only an abutment on the castle side remains.

The forework

The high entrance bridge was once wider and probably incorporated a drawbridge between two vertical piers. The pier closest to the castle extended above the road and formed a gateway that was still in place in the 1750s. Beyond are the remains of the great forework to the left and right of the access road, guarding the entrance. Immediately to the left is the high stonework of the original ‘Wall Tower’, or what became known as the ‘Lantern’ or ‘Lamp Tower’, the earliest part of the castle built directly onto the lower scarped rock. The forework formed a five-storey gatehouse over the entrance, abutting the red stone wall to the right, with its deep openings and projecting, rounded buttresses on its other side.

The ‘Modern House’ and the Great Hall

The only surviving building is, in contrast to the massive fragments of ruined walls and towers, a French-influenced two-storey house to the left of the courtyard. It was built by William Sinclair when he extended much of the castle between 1582 and 1597. It is likely to be his initials ‘WS’ with the shield bearing the St. Clair engrailed cross above the dormer window on the first floor. The house was improved by his son, Sir William Sinclair of Pentland, who had his initials ‘SWS’ and 1622 carved into the lintel above the doorway. The niche above the door probably held the armorial bearings of the family.

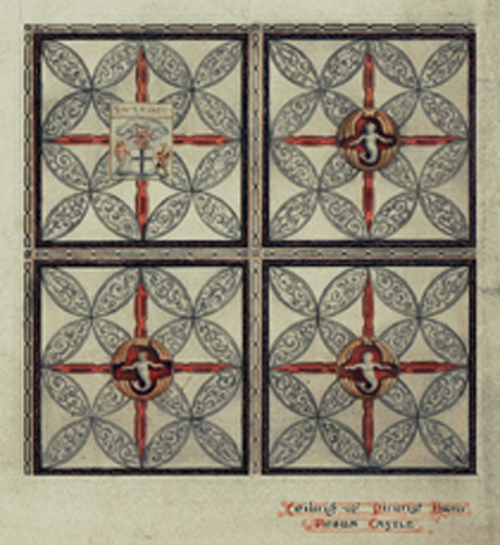

Inside, the entrance gives way to a small hall, from which a wide staircase to the left leads to the bedrooms above. At the foot of the stairs, a small antechamber leads into the principal room of the house. This used to be a withdrawing room or a dining room, accessible separately from the rooms above by a spiral staircase (visible externally as a stair turret). The ceiling of this room is comprised of nine panels, originally highly decorated plaster with hunting and hawking scenes and floral ornamentation, but now painted white. At the centre is the only representation of the arms of Sir William St. Clair of Pentland to have survived from that time (reproduced above), likewise dated 1622.

Immediately to the right of the entrance hall is a doorway to a narrow kitchen, and to its left, an eighteenth-century panelled dining room. Visitors are unlikely to realise that this room and the modernised kitchen are all that remain of the ‘Great Hall’ built by William Sinclair in 1597. Beyond, where the rest of the room is roofless, a fireplace bearing a shield with his arms and that of his first wife, Jean Edmonstone, can still be seen. In an attached corner tower, diagonally opposite the fireplace, there used to be a private room and another spiral staircase that led to the floor below and possibly above, if there was an upper floor.

he built the vaults and great turnpike of Roslin; upon the laft, his name and arms, with the arms of his lady, are as yet feen. He builded one of the arches of the Drawbridge, a fine houfe near the Milne, and the Tower of the Dungeon, where the clock was kept. The initiall lettres of his name are graven on a ftone above the dyall, with the following, 1596, which defigns the year wherin that worke was finished.

The lower floors and the Great Turnpike

The three floors below the ground-floor of the house can only be reached by the ‘Great Turnpike’, a four-foot-wide stone staircase, accessed from the entrance hall. These stairs lead directly to the basement, where the original kitchen and three rooms are entered from a single dark passage. The kitchen’s giant fireplace is large enough to cook an ox, and has channels cut in its stone hearth to drain fat and other liquids to the outside wall. The bakehouse above the kitchen contains a large oven and the other rooms on this floor and that above are laid out to a similar plan as those below, with access to cellars in the two lowest floors of the attached tower. Three-foot-square openings were cut in the ceilings at each landing, probably to allow a rudimentary lift to service the upper floors. The passage on the middle floor ends with a sealed doorway leading to higher ground outside, through the ‘Old Guard House’, close to an ancient yew that is said to be almost as old as the castle itself.

The small windows overlooking the Esk on these lower floors provide little light, so the rooms and passages were probably lit by Scottish crusie lamps, iron lamps with rush wicks. They are now cold and damp, but when the kitchen fire was blazing, its heat must have warmed them. The top floor, the last before re-entering the house, was used by domestic staff. It was probably from a now-sealed door in its passage that the vaults under the courtyard could be reached.

The Keep and wall walk

The ‘Keep’ or ‘Great Dungeon’, built about 1390, would have towered over the courtyard, until it was reduced to rubble by the English in 1650. It was also known as the ‘Clock Tower’ or ‘Bell Tower’. An exit on the third floor opened onto a wall walk leading to the forework, where the buttresses or ’rounds’ created recesses, or galleries where they were enclosed by ‘tourelles’. It was said that this wall was part of a chapel when the castle was first built, but it is unlikely to have been more than an oratory. Later, the space between the Keep and the forework may well have been domestic quarters before the ‘Modern House’ opposite was built. Although there is now no trace, another earlier building might have filled the gap between the forework and the ‘Modern House’.

The gardens

Below the castle walls, the land leading to the river’s edge and the linn was used as gardens, providing food for those living at the castle. Certainly, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries there would have been many people at the castle dependent on the St. Clairs for their provisions. (The strawberries were still attracting visitors from as far afield as Edinburgh in 1815!) Historical references have been made to an orchard that was planted below the castle and extending to below Rosslyn Chapel.

The linn

It is believed that, long ago, the linn created a barrier to the river and most of the low-lying land upstream was below water, forming a lake. As the area slowly drained over the years, it became marshy (and called the ‘Stanks of Rosslyn’), finally drying out. Their are indications that a timber bridge was built on the great blocks of stone forming the linn, providing access to the castle from this direction. A few remains of the mill close to the linn can still be found, a passageway and steps cut through a rock and a water course, but there are no visible signs left of a ‘fine house’ or other buildings.

The area upstream of the linn is now part of the Roslin Glen Country Park (also see Friends of Roslin Glen and the Esk Valley Trust) which is the beginning of an outstanding scenic river walk from the ruins of the Roslin Gunpowder Mills, through what used to be a carpet factory and cottages (now a car park), across the North Esk, around the castle, below the chapel via Gardener’s Brae, and to Hawthornden and beyond.

Oh, Roslin! time, war, flood and fire,

Have made your glories star by star expire.

Chaos of ruins! who shall trace the void,

O’er the dim fragments cast a lunar light,

And say, ‘here was or is,’ where all is doubly night.

Alas! thy lofty castle! and alas!

Thy trebly hundred triumphs! and the day

When Sinclair made the dagger’s edge surpass

The conqueror’s sword, in bearing fame away.