William ‘the Waster’ Lord Sinclair

In 1476, William Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, resigned his Caithness earldom back to the King and received a new grant of it, with the remainder to William, the son of his second marriage to Marjorie Sutherland. The baronies of Roslin and Herbertshire in Stirlingshire were resigned and re-granted in a separate charter, with the remainder to his son Sir Oliver, also from his second marriage. With the most prestigious properties going to Sir Oliver and his brother-german William, it effectively disinherited William, his eldest son by his first marriage to Elizabeth Douglas. The elder William had always described himself in charters either as ‘Master of Orkney and Caithness and Baron of Newburgh’ or ‘son and apparent heir’ of Earl William; he clearly had an expectation of receiving the most prestigious portion of his father’s estates, befitting an eldest son. In 1476, Earl William thought he had done his best to prevent his eldest son from frittering away the earldom and baronies which he and his ancestors had spent so many generations accumulating, but that was not to be.

Following his father’s death sometime before July 1480 and probably with the help of his eldest son Henry, who of course had his own vested interest, William ‘the Waster’ disputed the right of succession with his half-brother, Sir Oliver of Roslin. Agreement was ratified in February 1481 that William should have Cousland in Midlothian, Dysart plus Ravenscraig Castle and the adjacent lands of Wilston, Carberry and Dubbo in Fife. This was on condition that he and his heirs gave up all rights to the barony of Roslin, the castle, the chapel, the lands of Pentland and Pentland Moor in Midlothian, Morton and Morton Hall in Edinburgh and the barony of Herbertshire in Stirlingshire and that if he or his heirs made any claim to the earldom of Caithness, Sir Oliver would remain impartial in any dealings between his brethren.

Despite this agreement, a little over a year later, a brieve was issued from the Chancery of King James III to the Sheriff of Edinburgh to organise a trial by jury of Lord William Sinclair. Seemingly, Sir Oliver and the younger William, Earl of Caithness, would have been forced into this action if Lord William and his son Henry were demanding more recognition as senior heirs of line and attempting to make a claim to the earldom of Caithness. On 17 April 1482, a jury of fifteen nobles decreed that William was ‘non compus mentis et fatuus’ – a legal term meaning they found him of unsound and foolish mind, adding that he had been a ‘waster of his lands and goods for the previous sixteen years’, i.e., since 1466.

That year is particularly significant in that it was in Orkney, in October, that Lord William captured Bishop William Tulloch, took him from St Magnus Cathedral, threw him into prison in chains (probably in Kirkwall Castle) and ‘forced him to take certain oaths’. King Christian of Denmark and Norway was rightly outraged since the Bishop, despite being Scottish, was in the employ of the Danish King. As soon as he found out, Christian despatched letters of complaint to King James II in May 1467. By that time the Bishop had been imprisoned for several months, although he was certainly free by June 1467, when he is recorded as being in Shetland. In addition to the political turbulence caused, it seems revenge was the prime motivation; a few years earlier, Bishop Tulloch had sworn an oath of fealty to King Christian and been rewarded with the gift of some rents from Orkney, to the detriment of William’s father’s income. With Bishop Tulloch not to be trusted now he was King Christian’s sworn man, and the lawman in Orkney also complaining to King Christian that he was being impeded in collecting the King’s annual rents, probably William ‘Master of Orkney’ felt he should take action on his father’s behalf, however misguided his actions were.

His father, the Earl of Orkney, was certainly in a treacherous position serving two royal masters and, moreover, the King’s determination to ensnare the northern isles as part of Scotland was already clear; Earl William was well aware his Orkney earldom was about to be compromised as a result of the lengthy negotiations between the two countries. As a backup plan, he was already cannily buying up land in Orkney to offset his eventual loss of rent from the northern isles. In the end, King James II sent an embassy (which included Danish-speaking Bishop William Tulloch) to commence marriage negotiations between himself and King Christian’s daughter, Margaret, on 28 July 1467. Ultimately, Lord William’s capture of the Bishop did not help the Sinclair cause; instead, it galvanised the Scottish King into more determined action.

To backtrack a little, papal dispensation was granted for Earl William’s marriage to Elizabeth Douglas ‘to continue’ on 12 August 1432. As they were already married before that date, we can only speculate as to when William and his two sisters, Elizabeth and Catherine, were born, and in which order. William’s first mention in extant records was in 1456, likely by then to have been in his early twenties, when he ‘forcibly’ took the price of his mother’s terce of Mar [the life rent of a third of her previous husband’s lands] from William Seton of Echt. Elizabeth Douglas had rented the lands to William Seton’s brother, Alexander Seton of Gordon, who had since died. Elizabeth Douglas had also died sometime before November 1451, so the non-payment of rent must have been going on for a few years before her son William sorted out the problem in 1456.

Another more politically sensitive incident occurred in the autumn of that same year, when there was an attack on Björn Thorleifsson, the Governor of Iceland – another Danish official, whose ship was sheltering from bad weather in Orkney on his way to Denmark. Not only were his personal effects and furnishings seized, along with the royal tributes and ecclesiastical rents, the Governor, his wife and their entire household were imprisoned. King Christian protested by letter in April 1457 and although neither Earl William nor Lord William were actually named, the attack on the Governor is very unlikely to have happened in Orkney without the Earl’s consent. The incident is generally considered to be deliberate mischief-making by Earl William and his son, an attempt to sabotage discussions with the Danes regarding the Scottish crown’s non-payment of the ‘annual’ according to the Treaty of Perth. Negotiations were indeed delayed for two years.

Sometime between April 1458 and March 1459, Lord William married Christian Leslie, daughter of George Leslie, 1st Earl Rothes and Christian Halyburton, and in November that year, he and his wife were jointly confirmed in the barony of Newburgh in Aberdeenshire, centred on the tower house of Knockhall, the lands of Carten-Sinclare[1] in Stirlingshire, plus £20 annual rent from the lands of Dysart in Fife. In a charter dated 13 February 1463 at Carten-Sinclare, Lord William sold both Carten-Sinclare and Yemy in Lennox to Malcolm McClery, the first of many land transactions over the years. By 1474, Lord William was raising money against the fishing rights on the river Ythan in the barony of Newburgh. Eventually, in 1478, these were sold to James Ogilvy of Deskford with a reversion and were ultimately bought back by John, 9th Lord Sinclair, in 1630, prior to his selling the entire barony of Newburgh to the Udny family a few years later.[2]

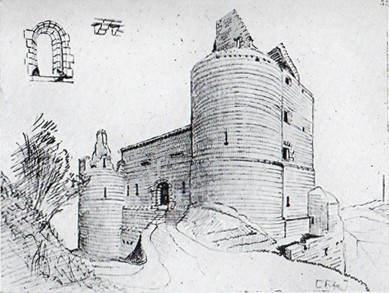

In 1481, Lord William had acquired the lands of Cousland, Ravenscraig castle, Wilston, Carberry and Dubbo in Fife, through his settlement with his half-brother, Sir Oliver. That settlement was not quite as straightforward as it could have been. In March 1483, Earl William’s widow, Janet Yeoman, the Countess of Caithness, sued John of Wemyss and David Barclay for wrongfully withholding her terce of Dysart, Brunton, Johnston, Ravenscraig, Wilston, Carberry and Dubbo in Fife. Although John of Wemyss and David Barclay declined to appear before the Lords of Parliament, their master, Lord William did. Despite his verdict of idiocy, he represented his case before the assembled Lords, asserting that Janet had already given up her terce of these lands and been paid for them. In judgement, the Lords decreed that unless Lord William could legally prove Lady Janet had given up her terce and taken money instead, she should receive the withheld terce money from John of Wemyss and David Barclay for the previous three years.

Undeterred, Lord William did not give up; in June 1483 he sued Lady Janet for withholding a third of Cousland, Dysart, Ravenscraig, Wilston, Carberry and Dubbo, totalling £134 and 53 bolls of wheat and barley, and at the same time, he sued Sir Oliver of Roslin for not delivering to him the sasines of said lands, which he contested was contrary to Sir Oliver’s obligation in their settlement of 1481. All three parties were present and, after much deliberation, the Lords decreed that Lady Janet was legally entitled to her terce of a third of the lands of Cousland, but she had not legally been served with the King’s brieve entitling her to the third of the other lands in contention, therefore she must in future refrain from collecting from them. Also, the Lords decreed that Sir Oliver had no case to answer on the charge of not serving Lord William with the sasines, as Lord William admitted under questioning that both he and Sir Oliver had agreed previously that the sasines were to be destroyed and he accepted they indeed had been – perhaps a memory failure on Lord William’s account.

Finally, in October 1483, Lord William pursued the persons who gave Lady Janet the brieve for Cousland, contesting that it was in error because they had served Lady Janet for the whole barony of Cousland rather than just her third; the Lords decided Lady Janet’s terce was of no value in future. This was certainly a complex legal tangle complicated by the transfer of Cousland and the Fife lands from Sir Oliver to Lord William after Earl William’s death and we have no means of knowing whether some other means was found to provide Janet with an income until her death.

In 1486, Lord William resigned Wilston and Carberry in the barony of Ravenscraig, and in July 1487 he sold Archadlie (or Ardkelly, granted to his gt-gt grandfather in 1348) with part of the fishings on the river Ythan to Patrick Gordon of Methlik. On 30 September the same year, he granted the right to William Hay, Earl of Errol and Constable of Scotland, to redeem the mortgages on Meikle and Little Haddo in the barony of Newburgh and enjoy the fruits of the lands himself.

Lord William lived beyond his means and his moniker of ‘the Waster’ is no doubt justified. He died sometime after 30 September 1487 when he signed the documents for Meikle and Little Haddo but before 8 January 1488, when his widow, Christian Leslie, was confirmed in possession of the barony of Newburgh. He was apparently buried at Dunfermline according to Roland Saint-Clair, although I have found no evidence to corroborate this.

On 14 January 1489, William’s eldest son, Henry, became 3rd Lord Sinclair and ‘chief of that blood’. His second son, Sir William of Warsetter in Sanday, Orkney, became a powerful and very able administrator on behalf of his elder brother, who held a lengthy tack of Orkney and Shetland from the King. He was also the ancestor of many landed Sinclair families in Orkney. Lord William had another son, Magnus, witness to a charter in 1487, but nothing else is known of him, and a daughter, Elizabeth, who married John Glendonwyn of Glendonwyn [Glendinning] in Dumfries and Galloway.

Notes

[1] Variously known as Carden, Carten or Garden and apparently gifted to a Henry St. Clair of Roslin by King David I, after the ‘battle of Allerton’ [aka Battle of the Standard 1138] per Saint-Clair of the Isles, p. 269. No documentary proof seems to exist to prove how the Roslin family acquired Carden.

[2] Cousland remained with the Lords Sinclair until July 1493, when Lord William’s son, Henry, sold it to William Ruthven.

Nina Cawthorne, January 2021